Robotics companies have dubbed 2026 the year of the humanoid, but manufacturers are not convinced.

Over 16,000 humanoids were installed worldwide in 2025, driven by demand from data collection and research, warehousing and logistics, manufacturing, and the automotive industry, according to technology research and advisory firm, Counterpoint. Humanoid installations are expected to surpass 100,000 across these industries by 2027.

The question is not whether humanoids are coming, but what they will be good for. For those eagerly waiting for consistent labor in manufacturing environments, humanoids seem like a great solution — but many say the technology is in its infancy.

“I want people to adjust their expectations a little bit,” Ken Goldberg, Ambi Robotics co-founder and William S. Floyd Jr. Distinguished Chair in Engineering at UC Berkeley, said. “Right now, they are most often hearing one side saying ‘this is going to happen.’”

As humanoids are piloted on manufacturing lines, experts are raising concerns that the hype around humanoids is outpacing their ability to create value in real-world factory environments.

Companies across the tech world are focused on humanoids, ranging from Unitree, Tesla, X1, and Boston Dynamics. Goldman Sachs estimates that selling humanoid robots will be a $38 billion industry by 2035.

“Factories aren’t chasing novelty—they’re chasing predictability,” Jonathan Hurst, Agility’s Co-Founder and Chief Robot Officer, said in an email to Build Better. “What customers want most is guaranteed labor: consistent output without absenteeism, turnover, or physical strain.”

Once humanoids are ready for mass deployment, these robots are expected to help close the labor gap and reduce labor costs; however, development remains in early stages.

Many companies are dealing with an autonomy gap, in which humanoids are still dependent on supervision.

Humanoids now have intelligence and perception similar to humans, but handling and battery life are still preventing widescale use, Bain and Company, a global management consulting firm, explained in their 2025 Technology Report.

Battery ability is not yet able to support a fully autonomous humanoid for long shifts, with each charge only offering up to two hours of operating time without being plugged in, Bain and Company explained.

These robots are also facing compatibility issues with existing workflows, along with many models struggling with dexterity and adaptability in unstructured environments, Gartner, a business management consultancy, reported.

Before humanoids are ready to deploy on a mass scale, Goldberg believes companies have to collect more data.

“We have to make them a lot more reliable,” he said.

Some companies are actively selling humanoids to manufacturers, and remain optimistic that the humanoid revolution is here.

UBTECH, a robotics company based in China, sold over 500 industrial humanoids in 2025, and expects to sell even more this year, PR manager at UBTECH, Wenyi Rao, said.

“We have seen a lot of devices like industrial robots or robotic arms in factories for years, but there are still jobs that need to be fulfilled by human workers,” Rao told Build Better. “Those industrial robots are mainly set to complete specific tasks, but humanoid robots, with growing embodied AI capability, are able to complete a series of different tasks.”

UBTECH released its latest humanoid in July 2025, dubbed the Walker S2. The model is capable of loading and unloading boxes, sorting, and quality checking. The robot can also monitor its power level and choose to autonomously switch out its battery.

The Walker S2 model goes for around $180,000 per robot, which, for most human labor on the line, is still too high for a reasonable return on investment. UBTECH also offers its robot through Robot-as-a-Service, which is a subscription-based model that allows manufacturers to lease humanoids for $5,000 per month.

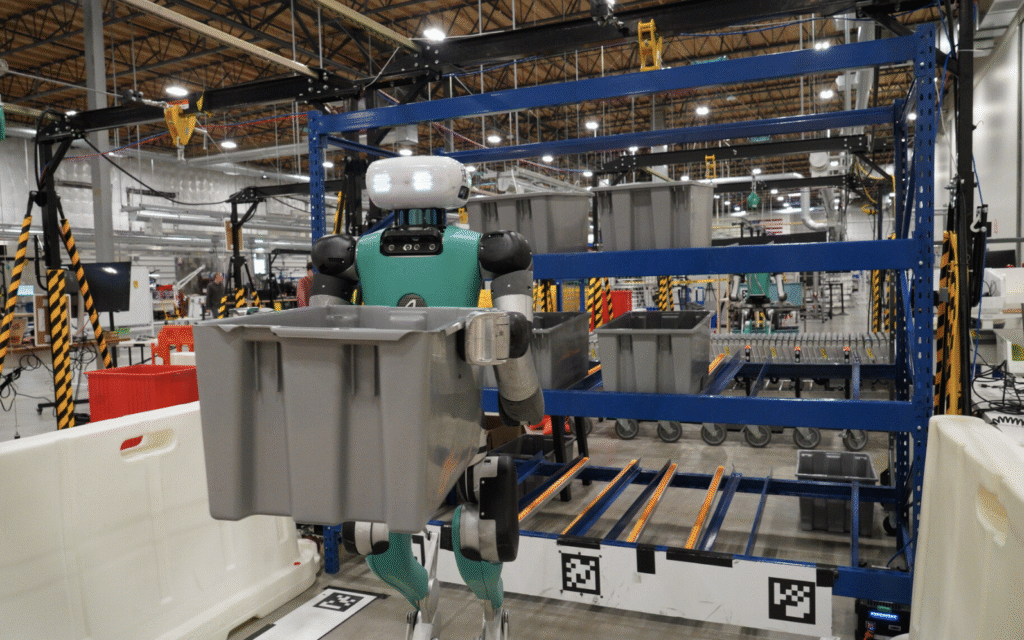

Agility Robotics is another major player in the humanoid space. The company has deployed its robot, Digit, to various manufacturing plants and has also built the first full-scale humanoid robot factory capable of producing 10,000 robots per year.

Agility offers Digit through the Robot-as-a-Service model for around $30 an hour, which is comparable to skilled manufacturing labor rates in the United States.

Digit can autonomously undertake repetitive material-handling tasks like moving totes, loading and unloading carts, feeding machines, and transporting items.

Over the next year, the company’s engineers expect to improve the humanoid’s ability to tend machines, handle more complex tote flows, and enhance its autonomy.

“The goal wasn’t to mimic humans for novelty, but to solve real labor problems in human-centric spaces with minimal infrastructure change,” Hurst told Build Better.

Agility designed Digit to function in environments geared towards a person’s height and reach. With its human-like form, it can fit in aisles and reach shelving, carts, and tools.

“While wheeled robots excel in structured, fixed routes, legs outperform when environments change frequently or weren’t designed around automation, which is the reality in most existing facilities,” Hurst said.

Still, some analysts remain skeptical about whether the humanoid shape is necessary.

One expert, Allison Okamura, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Stanford University and Science Fellow at the Hoover Institution, believes that if a factory were designed from scratch, the humanoid form would not be considered ideal.

“Instead, you would use a more purpose-specific robot or machine for better accuracy and efficiency and lower costs,” Okamura said.

Gartner analysts found polyfunctional robots as an impressive alternative to humanoids because they do not rely on a human shape, instead potentially offering wheels and a telescopic arm to complete the same tasks.

Hurst does not see that as a viable alternative.

“Digit is designed for jobs that require moving through space, reaching where humans reach, and adapting to different workflows without retooling,” Hurst said. “Unlike fixed automation infrastructure, Digit can perform one task in the morning and a completely different one in the afternoon.”

There is no definitive answer on when humanoids will be ready for mass deployment onto the factory floor.

Despite rapid investment and improving capabilities, today’s humanoids are best suited for repetitive material-handling tasks. The robots function well under a supervised operation with limited autonomy and restricted operating endurance in real factory settings.

Goldberg is not optimistic that humanoids will be ready anytime soon.

“It is not going to happen in a year, not in five, probably not in 10,” Goldberg said.

Eric Klein, a managing partner at the venture fund, Mucking with Gravity, told Build Better that humanoids are still five to seven years out from mass deployment.

Meanwhile, Matt Culver, a mechanical engineer at Seacomp told Build Better he believes humanoids are over two years off.

“Hardware is the limiting factor,” Culver said.

With many humanoid demonstrations teleoperated by people, manufacturers need to watch for when a humanoid has true autonomous dexterity.

“Robot hands need more accurate, smaller, and less expensive actuators and sensors that can be manufactured at scale,” Okamura said.

Hurst believes safety certification, large-scale reliability, and real-world deployments will help abate humanoid doubt.

“When humanoids quietly become part of daily operations, skepticism fades,” Hurst said.