Manufacturing has countless operational frameworks. From the Five Whys to Six Sigma to 8D problem solving, each team has adopted their favorites, each team adds their own touch — and in the process, many teams accidentally introduce or eliminate steps that create more chaos than calm.

Sound familiar? It does to Sam Bowen. Sam’s career has taken him to Amazon, Fitbit, Tonal and Peloton, where he’s worked as a hardware development leader to build industry-defining consumer products and nurture strong manufacturing teams. He grew the Amazon hardware team from 5 to 80 people, Fitbit from 15 to 250, and Peloton from 50 to 250. He knows how to scale, and he knows how to do it methodically.

While building these teams from the ground up, he developed a deep appreciation for all kinds of problem-solving, and adopted 8D as his personal model. We sat down with Sam to learn about his team-building experiences, and how he has leveraged 8D to build teams of highly methodical problem-solvers.

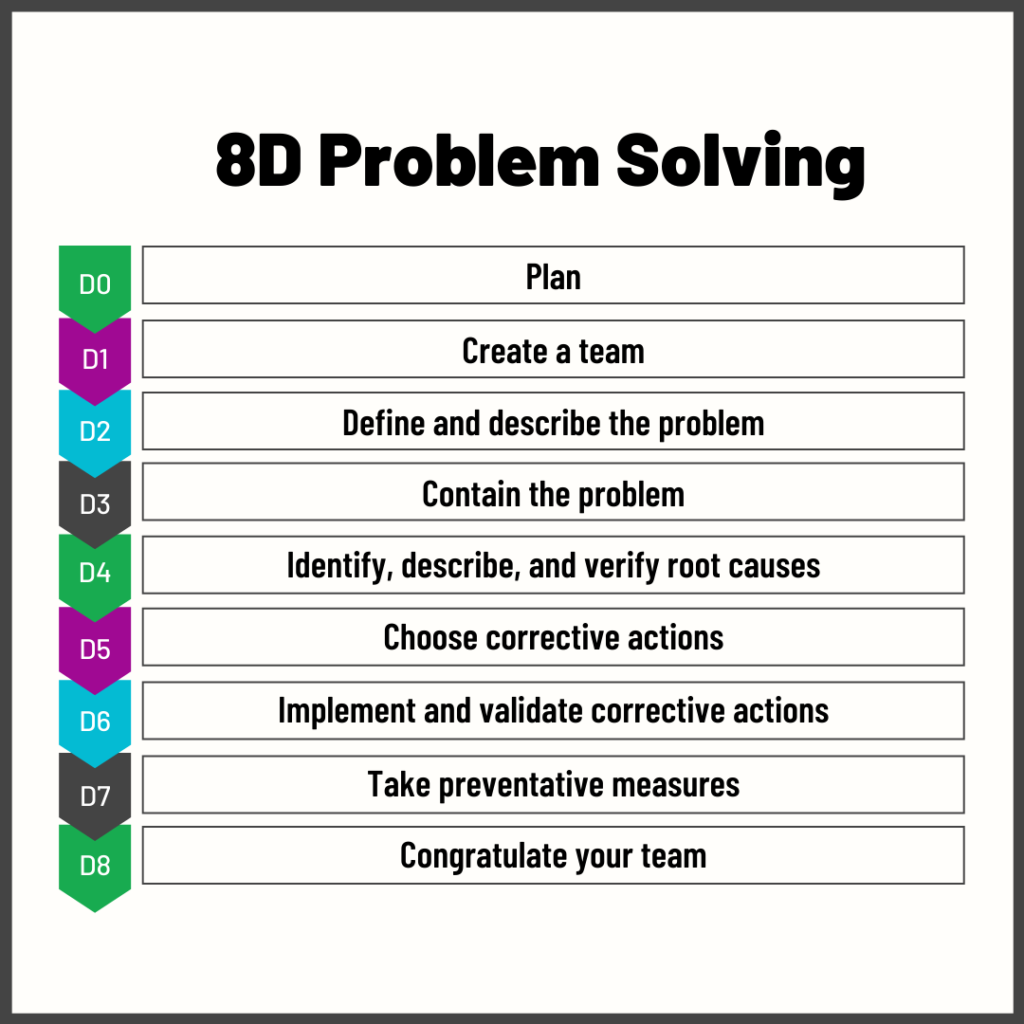

What is 8D problem solving?

The 8D approach is a problem-solving methodology that follows eight disciplines to help teams identify, correct and eliminate recurring issues in manufacturing.

Sam Bowen uses 8D to solve a variety of manufacturing challenges.

It looks intuitive at a first glance: you plan your approach, describe and contain the problem, verify the root cause, and take specific actions until it’s resolved. But because it’s deceptively simple, Sam finds that it’s easily dismissed, and many teams incorrectly think they’re already following those steps.

Where’s the disconnect? He’s found one common thread with the most challenging steps for teams to implement: those that require a “stop.”

Stop your people: Create a team

The first steps in the 8D problem solving model is to create a plan to solve the problem, which includes identifying the right people to solve it. Sam believes that the simple act of stopping and assessing who is needed on a problem-solving team is critical and often overlooked.

In fact, Sam has watched disasters happen because even within one company, each team takes a different approach: when a failure is identified, the manufacturing team might start adjusting processes, or the engineering team might dive into CAD to experiment with design changes. Both teams then think they’re making progress, when in reality, there’s no structure or communication around the problem they’re trying to solve in the first place.

Sam Bowen (center) with an engineering team in Tsingtao, China in 2001. He was onsite for six weeks to start up the EVT line for a UK-based cellphone developer.

While these communication problems are frustrating, they’re also completely understandable to Sam. He knows that each team has different metrics of success and approaches problem-solving with their own bias. If you’ve been battling adhesive issues on a PCB, you may think that’s causing the failure. Or, if you had concerns about a component from an upstream supplier, you may think that component holds the answer. And while he understands the source of team confusion, he also recognizes the costly ripple effects.

“No matter the reasons, failure to communicate creates a big mess,” Sam said. “That’s why this first step to create a plan is so powerful. It causes everyone to stop and define the team before any problem-solving takes place.”

Stop the line: Define containment

Despite the differences between engineering and operations teams, everyone in manufacturing agrees on one thing: do whatever it takes to avoid stopping the line. Stopping the line impacts shipment schedules and reduces product margins. Worst of all, a stopped line may be difficult to get running again, because operators with experience on that program might have been reassigned elsewhere. Since everyone is hardwired to avoid stopping the line, it’s especially challenging to decide when it is necessary. That’s where discipline three in 8D problem solving comes in: define the containment plan.

Sam says it can be easy to run to failure analysis early on, but that containing the problem will ensure the customer is protected from a range of product issues, from defective to safety-critical.

Using 8D to stop the line at Peloton

Sam Bowen makes the call to stop the line about once a quarter. It’s never easy, and it has taken time to build trust with his team members that he was making the right call. In one particularly memorable experience early on at Peloton, his team discovered the pedals on the Bike Plus weren’t performing properly under certain mechanical tolerance tests. But the bikes were already in mass production.

“I approached the operations team and delivered the bad news that we had to stop the line — we couldn’t use the pedal, and we had to go back to the old pedal,” Sam said. “I knew it meant shipment wasn’t going to happen on time, but we needed to do it.”

While Sam might have been ready to stop the line to contain the problem, the operations team wasn’t. They didn’t pivot until a month later when more data came in that proved it in fact needed to be changed. At that point it was a scramble to order the replacements and release them to production.

“It all ended up working out, and our team grew together out of that experience, but it could have gone very differently if we had stopped the line sooner.”

Stop the problem from repeating: Take preventative measures

The seventh discipline in 8D problem solving is “take preventative measures,” where teams change the operation systems and procedures to prevent the problem from happening again. This is where leaders can define their problem-solving culture — because culture doesn’t develop when you’re fighting the fire, but after the fire is put out and teams have room to assess what went well and what went wrong.

Sam tackles this discipline with retrospectives. In most retrospectives, everyone trudges to the meetings expecting finger-pointing, and in many cases, that’s exactly what happens (if a retrospective happens at all). He sees a better way to do it.

“The main challenge with retrospectives is that the problem isn’t clearly defined,” Sam said. “Do we look at the schedule, the product, the cost? It’s too broad. The biggest thing you can do to improve your retrospective is to frame the problem.”

It’s important to frame it around a problem that’s different from the one identified in step two. For example, while step two might explore why a unit is failing a drop test, step seven should be broader: why did the project launch three months late, or why did the program not meet cost targets? Identifying one question anchors the retrospective so team members rally instead of pointing fingers.

8D problem solving protects the customer

Manufacturing teams don’t have to live with chaos. It’s a lesson Sam learned early in his career from Jeff Cantlebary, operations manager at Amazon (now at Snap). Sam saw Jeff bring order and calm to countless challenges during their time working together, using 8D problem solving as a foundation. He also credits Jeff for teaching him another valuable lesson on the relationship between manufacturing leaders and customers.

“Jeff is a very smart, thoughtful person, and he brought everything back to one goal: protect the customer. Once I saw how powerful that was and how 8D helped me do that, I was all in,” Sam said. “It’s worth the time investment to stop, slow down and be intentional about problem solving so you can both protect your customers and deliver meaningful customer experiences.”

Related Topics