A version of the following article originally appeared on Forbes.com.

It’s extremely difficult to ship hundreds of thousands or even millions of things with high levels of quality. Even with stringent standards, brands carefully watch their return metrics (known in the business as TWR, or total warranty returns) to make sure that their quality control systems are working. The manufacturing industry has a bit of a reputation for being a slow-moving industry, and the consumer electronics vertical is no exception. The world outside of manufacturing has changed significantly in the last ten years, and manufacturing systems frankly haven’t kept pace. Engineering teams for new products are being asked to do significantly more year after year – thinner, faster, and better – with almost the same resources and toolsets. In the last few years, Amazon reviews have become a new manufacturing KPI, as they work to make perfection possible.

Five years ago, the brand’s most trusted engineers would spend hours at the end of the assembly line inspecting units from the final development build, days before the product was going to roll into production. They would sift through tens or hundreds of trays of carefully wrapped units for the absolute best: the ones with smallest gaps and offsets, no scratches or dents, best button feel, and of course, representing the best function possible. Once selected, these “golden units” would be carefully packaged in retail packaging and sent to technology reviewers, who would then write the reviews that drove demand for the product.

While this process continues today, and the technology reviewer still plays a large role in driving initial demand for a new product, a democratization has occurred that no one in manufacturing is talking about: the very real business impact of bad Amazon reviews. Have you ever picked between two similarly-priced products on Amazon with thousands of reviews and just blindly chosen the one with higher reviews? So do millions of other people.

I’ve been in the consumer electronics industry for nearly a decade, but was only introduced to this shift recently. I was speaking to a senior manufacturing operations leader at a global consumer electronics company, and was grilling him on how he would rank the relative importance of final yield during mass production versus TWR. He shook his head and told me, “the most important post-shipment metric is Amazon reviews.” He went on to describe how this was a relatively new area of focus, and that they were still figuring out that some types of products were more sensitive than others. In particular, products entering crowded markets suffer the most, as well as products for particularly passionate tech-savvy users, like gamers. When I asked other leaders across the industry, they agreed: Amazon reviews are such a strong driver of sales (even for brick and mortar store sales), that a few bad reviews soon after a product ships can have real drag on the sales and resultant revenue for a new product.

I was speaking to a senior manufacturing operations leader at a global consumer electronics company, and was grilling him on how he would rank the relative importance of final yield during mass production versus TWR. He shook his head and told me, “the most important post-shipment metric is Amazon reviews.”

This stacks several key problems directly against the hardware brand.

First, consumer electronic products have strict buying cycles (Christmas is the big one), and therefore strict schedules to ship due to demands of channel partners like Best Buy and Walmart. Brands must deliver certain quantities of units on certain dates, whether the product is ready or not. This is such a problem that one former vice president at an entertainment consumer electronics brand said, “The dates couldn’t be moved. If the product wasn’t ready and we couldn’t hit the date, we would sometimes pull the product.”

Second, the most important reviews are the earliest ones, but the first units off of the line are the ones most likely to have issues. Ramping a new product with human assembly operators, the norm for consumer electronics, is a messy process. Some manufacturing assembly steps or processes take some time to settle in. While most manufacturers sort out as many of the defects with extra human inspection or testing, they’re financially incentivized to ship as many as possible as quickly as possible.

That leads to the third problem: perfection is really hard. Even the best quality control processes have escapes and dark yield, units that have defects that weren’t caught by the systems in place on the line and went to customers. Measuring dark yield is a really difficult thing to do by definition (since tests don’t catch these units), but operations leaders know it exists. They see it in the TWR rates. They see it in dreaded product recalls. Not all defective units shipped result in bad customer experiences, but some do. Based on studies done by Instrumental, Inc., dark yield rates can be four percent or even more of the total units shipped to customers. This is a non-trivial amount of liability floating around in the field.

Brands have taken notice of this new paradigm, and have taken the first steps to focus on it. Whereas five years ago they were able to focus on interacting with unhappy customers who left reviews on their own websites, now they mine the information left by customers on Amazon for clues. A former leader at a leading microphone brand said, “We look at Amazon reviews every day, and we will stop production if the defect rate gets high enough.” A vice president of operations at a top cell phone manufacturer said, “If you have consistent issues across the reviews, and the company doesn’t respond, this becomes a critical problem for customers.” He went on to describe one of the key benefits is that, “you can use Amazon reviews to quantify how bad quality affects your sales,” enabling leaders to justify larger costs to improve quality on the next product.

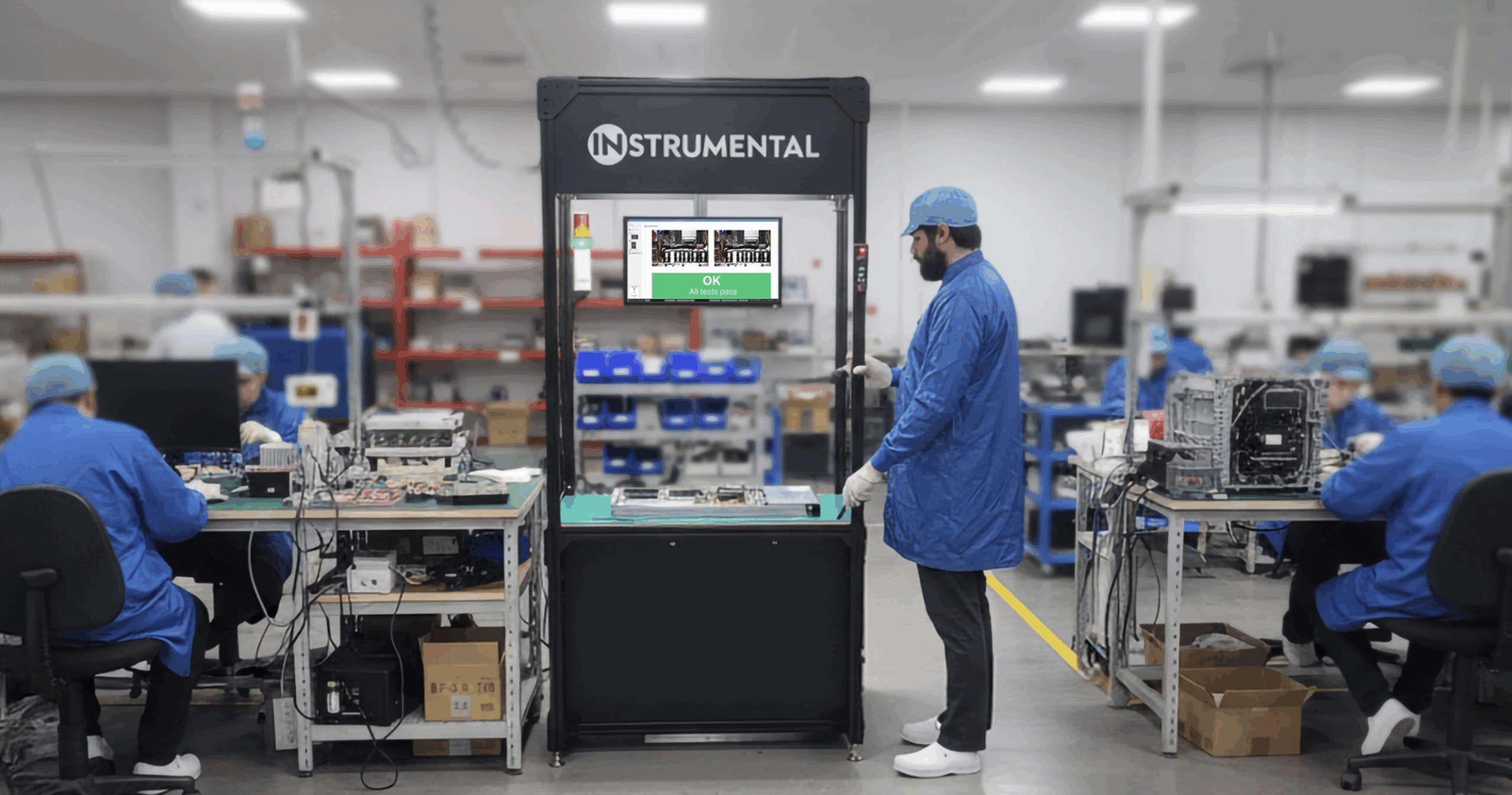

Knowledge is power, but the systems in place to actually improve quality in the manufacturing process haven’t kept up over the last five years. In the end, this creates a further squeeze on hardware development teams who were already being pushed to ship faster, and now have to be concerned about “onesie-twosie” failures on the line. Manufacturing needs better tools, not just to do the things that have always been done better – like replacing human inspectors with cameras – but to do things that haven’t been done yet – like detecting those dark yield issues or enabling teams to do more with less time in development.

Instrumental is the only product on the market that was designed to detect dark yield issues, and enable your teams to fix them fast.

Request a demo to see how Instrumental can enable your team to reduce dark yield issues during development and to minimize escapes during production.

Related Topics